The sorrowful keening of the crowd pierced the clear, dry air on the plateau. They huddled together, staining the dusty ground with their crying and the clear air with their wailing. It was the one day of the year when they could grieve, the one day it would not slow them down.

The wanderers had returned to the Maw.

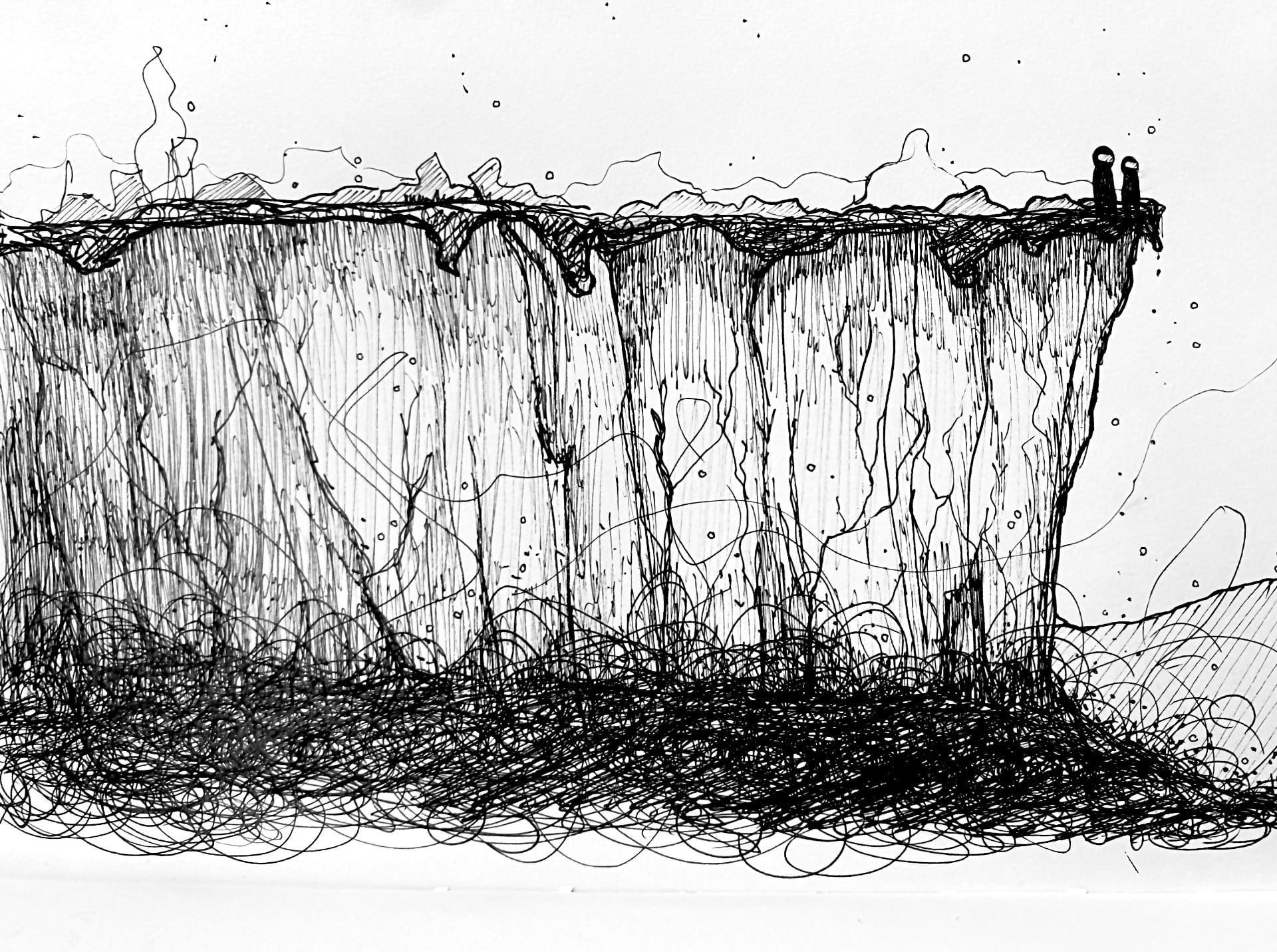

A rent in the land: jagged, and cruel like a wound upon the flat expanse of the dry highlands. Down below, a wisping grey-green fog swished about like a river of dandelion fluff, or the lethargic lifeblood of the world. Despite its tranquil innocuousness, one among the wanderers stared down at it with hatred. A hand, bony but strong, clenched on his shoulder. “Control yourself,” she commanded. “It is long to dark.”

The young man nodded, gritting his teeth.

***

They donned their masks with efficiency and precision, latches and clasps clicking together until the heavy constructions of leather, cloth, and metal were comfortably choking them. Pouches stuffed with perfumes and herbs bulged from the mask cheeks like organic protrusions. Their breath rasped out, while inhaling sanded their throats with spicy air. The young man’s words were shredded and torn as they fought their way through the mask, emerging with a bestial coarseness.

“Let’s torch it. Let the Maw choke on smoke. It deserves to die.”

Behind the domes of milky glass, the older woman rolled her eyes. She was starting to suspect she chose a poor apprentice. “It’s part of the cycle,” she said back evenly, and the young man thought the mask made her sound as weak as she was old.

They put up their hoods, hooking them into the cloth so their necks and the backs of their heads were covered. There was not an inch of exposed skin.

“It eats us,” the young man continued angrily. “It profits from our deaths. It’s a monster.”

“We profit from our deaths,” the woman whispered to herself.

They drove thick spikes of metal into the ground with hammers, then securely knotted rope around them. They tied the other end around their waists, and looked over the edge of the Maw, where moonlight made the fog below into a river of spoiled milk. “Start falling,” the old woman commanded.

Their rappelling was cautious, but not difficult. The walls of the Maw had ample handholds and ledges to stand on. The young man went faster, letting himself drop farther each time he pushed off the wall. The old woman was calmer, keeping watch on the light of the moon, making sure it would be just above them when they hit the bottom, giving them the strongest light. There could be no fire in the Maw.

The air grew moist and sticky as they approached the not-fog. There was the faintest sound in the air, like the flapping of the most minute wings. Instinctual revulsion had the young man breathing shallowly, afraid his filters would fail, and he’d inhale the spores around him. The old woman, trusting her equipment, continued her deep breathes, filling her lungs and her muscles with precious air.

“The stonemasons are going to stop feeding the Maw,” the young man said suddenly, quiet words carrying through the silent night.

“And what is it the stonemasons will do, instead?” They could not see each other, only the shadowy outlines of moving spore clouds.

“They’re making boxes of stone, so the Maw cannot eat the dead.”

“And where will all the boxes of stone go? The stonemasons are more numerous than us, and more prone to death. How long until they are crushed beneath the weight of their dead? Will they make roads and walls of their boxes of stone? A city of their dead, ever growing larger and heavier until the living can no longer bear the weight? Let the cycle cycle. Let the dead disappear.”

“Into a grim gullet,” the young man spat back.

Their boots touched the bottom of the maw, sinking into an unseen mulch. The young man looked down uneasily, expecting the ground to collapse in and consume him at any moment. He had been raised on the barren plateaus—ground was supposed to be solid. The old woman noticed but made no comment—her peace was long made with the components of her ancestors. In the ghostly moonlight, the Maw’s flora looked alien, vines creeping up the walls and flowers bursting from cracks in the earth.

The two kept walking, hanging to the nearside, where the valuable bodies were—those who were respected, or powerful in life. Those were lowered into the Maw by rope. The uncared-for’s bodies were tossed in, where they hit the far wall, and split open to feed the Maw their viscera.

The old woman walked past an old body; Mawshrooms had encircled and consumed it. Their caps looked like fleshy tumors. While the subtle flapping of a single Mawshroom’s gills was too quiet for humans to pick out, the countless number of them made a constant low susurration.

The two found the day’s bodies, the oldest of them just under a year dead. In the few hours since they had been let down, the Mawshrooms spores had taken root in their flesh, and tiny bulges like goosebumps promised they too would be consumed within time. The two picked at them for earrings, necklaces, bangles, and other valuables.

“Unnatural,” the young man hissed. “Disgusting.”

“It’s the most natural thing in the world.”

“It’s plants eating animals.”

“They’re more like animals than plants.”

“I know? That’s what I just said.”

The old woman rolled her eyes.

The graverobbers picked their way through the bodies, dropping ornamentations in sealable bags, to be dunked in water and cleaned of spores above. When only a quarter of the moon was visible, the old woman called their work done. They returned to their ropes and climbed back up. The return was far more strenuous than the descent.

At the top, the old woman unlatched her mask, sat down, and enjoyed the clear air. She removed from her pocket a rolled cigar, lighting it with a practiced hand. She took a deep puff. The young man held out a hand, “Mind if I have one?”

The old woman raised an eyebrow, removed another cigar, lit it against her own, and handed it over. The young man stared at the ember.

“You’ve always refused them before,” the old woman said, “Why now?”

The young man walked to the edge and stared down at the spores. “Don’t you know these rot your lungs?”

He threw the lit cigar over the edge.

Writer | Mike Rosenthal ’27 | jrosenthal27@amherst.edu

Editor | Bryan Jimenez Flores ’26 | bjimenezflores26@amherst.edu

Artist | Alma Clark ’25 | amclark25@amherst.edu