“No one and nothing, boy, we were born from a daisy.” It was in that way that my father grew up understanding that his mother was named Martiniana, who was from Veracruz but had moved herself to the state of Puebla during that great national conflict that would repeat itself every one hundred years when the people realized (months before being summarily executed) that they were being exploited by the wealthy, and that his father was Abram, son of the herb that also gave birth to the plague that killed Doña Fausta’s—Don Arturo’s mother’s—peach bearing trees. The entire town mocked him and some threatened him with pesticide when he approached, but no one had the heart to tell him that his father was not a wildflower human.

It was in this way that the countless ancestors and near-relatives spread across the world were untethered from my father in perfectly non-violent erasure and would never be tied together again. Erasure like that cannot be reversed, like taking a good idea written down and thoroughly scraping the paper of its ink and then being told to have the thought all over again. By the time Martiniana’s son had my sisters and I, the family tree had been so vigorously abandoned and mismanaged that no effort was made to remedy the trunk for years, and so the entirety of the family came to accept that somewhere, somehow, there had been a weed that gave birth to us all.

I traveled to their remote town to find it. I got a plane ticket from Newark to Mexico City, took the bus my father had taken twenty years earlier in the opposite direction en route to the United States—though he did not necessarily know it at the time—and dropped my things off in the stuffy little apartment I was able to book last minute in the outskirts of the city of Puebla. My mother had always said I could sleep in a matchbox as long as it was quiet.

“Tell them that your grandfather died by lightning strike. Everyone will know who Don Abram was when you tell them that his rifle burned its image on his backside,” my mom said right before I boarded my plane. I walked into three small general stores, each selling the same candies and groceries as each other, and the three owners had said that they were not from the area and wouldn’t know about any lightning-branded riflemen or walking flowers.

I walked into a small bakery where a large and tall man, dark in complexion like my mother and me, stood behind the counter bagging little conchas for the lady in front of me.

“We used to say he was related to those bastard weeds behind the giant wall that separated Don Arturo Cruz’s plot from mine.” He said it while he was picking his teeth.

I looked at the man like he’d spat on my food. I was happy I wasn’t as white as some of my relatives because I felt my face boil, and I forgot the half-finished coffee that stained my breath with its strong flavor.

My next stop was an old and well-established bar that, according to my mother, had been opened during the Revolution by a friend of Trasvilla himself—though reports on the matter cannot possibly be corroborated. I had promised myself to not let this one get me so angry.

The bar owner was worse. “I heard once that your great-grandfather had run with one of mine under Trasvilla’s army, but he died way before he could do anything for you.” Her laugh echoed in the massive wooden hall that could fit all the town’s working-age, and often did. “If you go ask the priest, he could dig up some parchment with chicken scratch for birth records. He once told me I was related to a very pious woman who gave for the shrine of St. Anthony!”

I worried that I would run into the same “no, we have as much of an idea as you do.” Still, I made my way to the church, went through the motions of a good Catholic, and waited for Father Timoteo beneath the statue of St. Anthony holding the Infant Jesus.

“…Do you worry you come from nothing, like the rest of us?” He almost whispered, but I knew he’d spoken to me.

“I am angry that I could cure my familial amnesia and will fail, Father.” I turned to him, a slender old man who’d long given up on raising his voice to show his disapproval.

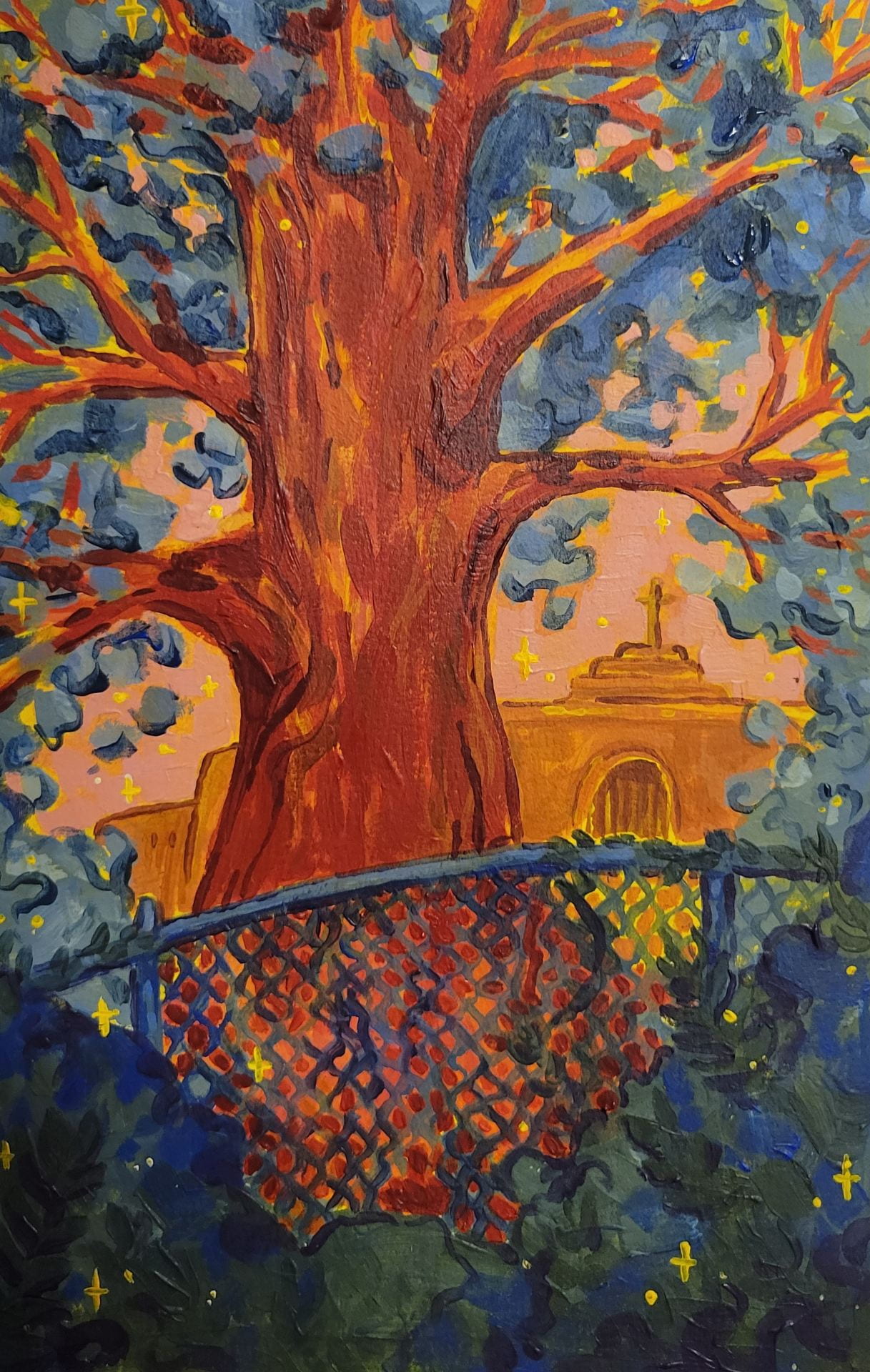

“Come with me, son, and you will see.” His steps were the loudest thing about him, and I could feel the lump in my throat ready to pop. He took me out of the church and walked me down a winding dirt road that fell off into the abyss on both sides. We walked and walked and walked and came upon a tree tightly strangled by metal fencing and yet tall as the David.

And without hearing what he was saying, I stared into the marred bark of the resilient tree and saw the faces of everyone I had seen in pictures: my aunt Loreta and uncle Pancho who’d sold their land; my cousin Pablo who’d gone missing; my mother, and sisters. We were all there and had been there for so long that it’d been forgotten. And we would be there forever.

Writer | Bryan Jimenez Flores ’26 | bjimenezflores26@amherst.edu

Editor | M. Lawson ’25 | mlawson25@amherst.edu

Artist | Piper Mohring ’25 | pmohring25@amherst.edu