I follow a mysterious woman draped in a navy-blue coat with a turquoise diamond pattern. The camera, like me, follows her steadfastly, focused on her hood, which bounces as she walks, until it falls off to reveal a messy bun of bright, blonde hair. She bolts towards the cliff, my heart matches her speed as she gets closer and closer without slowing down; I chase her desperately but the wind pushes me back until she stops dramatically at the edge and we are freed by the expansive horizon. She looks back, revealing her intensely green eyes, her head completely engulfed by the ocean in the frame.

“I’ve dreamt of that for years.”

“Dying?”

“Running.”

These were some of the first images I saw of Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Celine Sciamma, 2019) at AMC Sunset 24, before a screening of Parasite about a year ago. I remember my partner, who speaks some French, corrected the translation to English from the film’s original title, Portrait de la Jeune Fille en Feu. “That means ‘portrait of a young lady on fire’,” they said. I was impatient to see it from that moment and I ended up waiting a while. The anticipation ramped up as the buzz continued to grow from screenings all over the world. I kept waiting, but AMC seemed to have faked me out; they never showed it there.

It was not until late February of this year that I finally quelled my burning desire to see the film, and at that point it had reached legendary status simply because of the near impossibility of finding a screening. I could not get the final image from the trailer out of my head: a young blonde woman standing in darkness with a resolutely calm gaze as her dress catches on fire. I had to find out what that image meant. When I finally got to see the film, I felt like an old-fashioned cinephile who had traveled to a different country just to see a rare film even though it was only a 5-mile drive to the Tower Theater in Little Havana.

The Tower Theater is one of those old school movie auditoriums with a high ceiling and two levels of seating. There were not many people in the theater, and I was the youngest by at least 30 years. I sat alone towards the front of the second level. I love going to movie theaters alone; I feel truly anonymous, yet at home, as I submerge into the darkness of the room full of strangers. Without the self-awareness engendered by being around people I know, it is easier to lose myself in the film. Portrait of a Lady on Fire made this exceptionally easy. What Barthes would have called, the “brilliant, immobile and dancing surface” of the film instantly hypnotized me. My eyes bobbed up and down involuntarily along with the boat as Marianne, the main character, traveled across an intense aqua ocean to the remote villa. I sunk into my chair, paralyzed until the credits rolled.

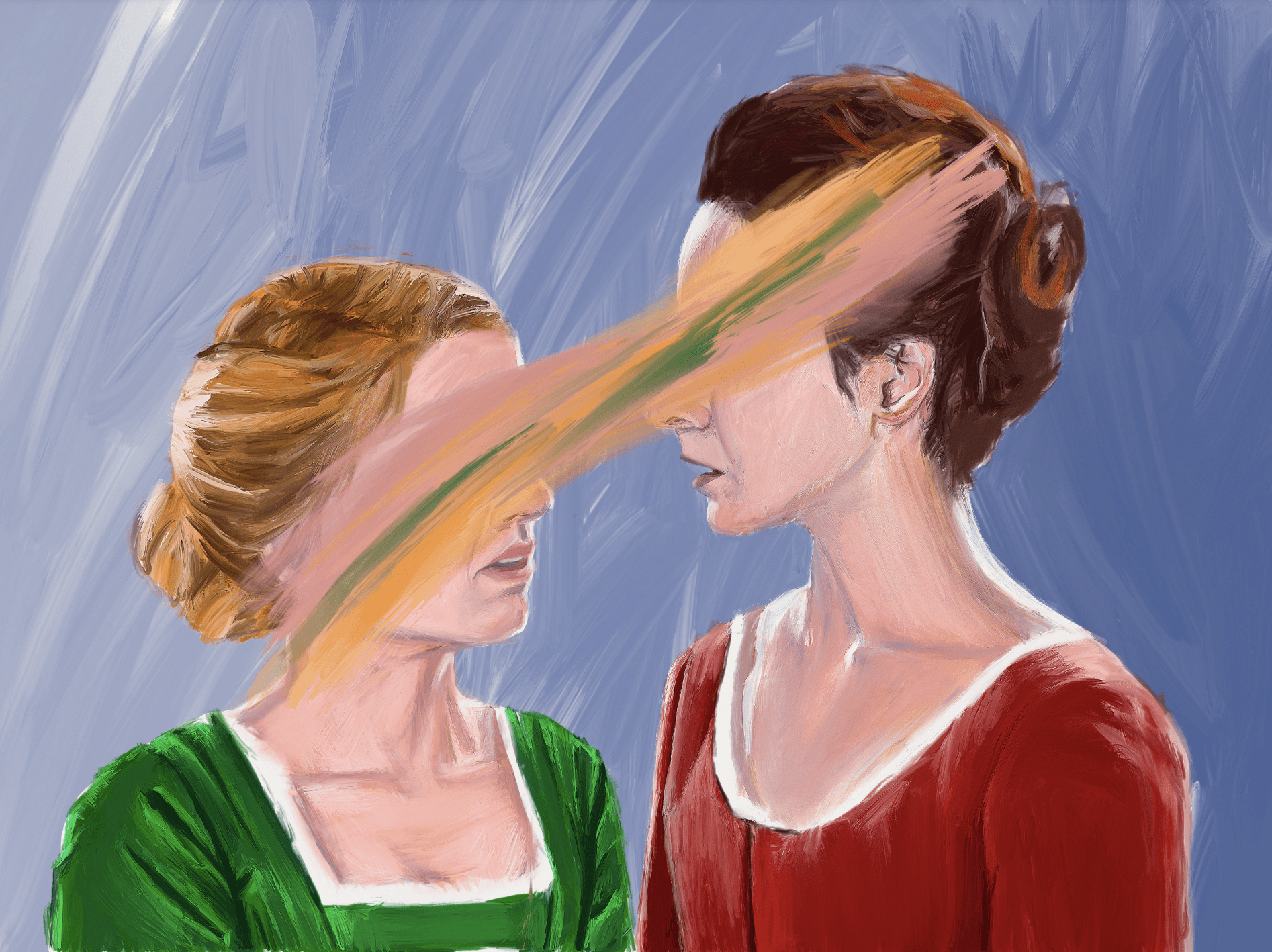

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is simultaneously a personal film and an epic. The film is about a painter, Marianne, who is hired to paint a wedding portrait for a woman named Héloïse. They fall in love but know their romance will be cut short by Héloïse’s inevitable marriage. The film tells a small and contained story with outsized emotions. The cinematography fluctuates between close-ups and wide landscapes like two different styles of painting to match this dichotomy. The screen dominated my entire field of view as I stared obsessively at each frame, hoping that each could stay in my mind forever. The fleetingness of the frames frustrated me but that’s also what made them so precious. Like Héloïse and Marianne, I knew my time was limited so I tried to take in every moment. I looked deep into Héloïse and Marianne’s eyes as they did the same to each other. The film turned me into a third participant in the romance, one who was both within and outside the film. Invited to inhabit their gazes,,I became as mesmerized as they were with one another. Each look communicated a myriad of emotions impossible to describe in words. I left the theater as if waking from a dream.

The film turned me into a third participant in the romance, one who was both within and outside the film

My memories of my experience with this film have become more surreal in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. Portrait of a Lady on Fire was the last film I saw in a theater. It’s been over 9 months. For this reason, any reenactment of the experience on a smaller screen would be underwhelming. I rewatched Portrait of a Lady on Fire in the Greenway dorms at Amherst College. The lights were on and I was not even close to being isolated. The experience was constantly interrupted by people speaking loudly about what they had done over the weekend or playing ping pong. However, it was still special to experience the film with others and if it were not for Hulu, I would not have been able to share this experience.

In his essay, “Everyone I Know Is Stayin’ Home: The New Cinephilia”, James Quandt laments popular cinema’s transition from a public and social experience into a domestic and isolated one. He claims that films cannot be truly appreciated and analyzed when in a digital format. For Quandt, the new cinephilia is one where iPhones and computer screens replace movie theaters. Girish Shambu has a much more optimistic definition of new cinephilia that he describes in his essay, “For a New Cinephilia”. Shambu sees traditional cinephilia as narrow-minded and as only one of many forms of love for film. To Shambu, new cinephilia is a direct response to old cinephilia, which is an ideology created by straight white men, largely concerned with the viewership of other straight white men. Old cinephilia emphasizes the technical aspects of film and the so-called purity of the theater experience. While old cinephilia often postures as apolitical, this guise further perpetuates its problematic ideals. In contrast, New cinephilia rejects the idea that films, both in content and viewing contexts, are neutral or apolitical sites. It explicitly values diversity in voices and celebrates film’s digitization for increasing accessibility.

On one hand, so much of the enjoyment of Portrait of a Lady on Fire comes from the visual experience, and the movie theater enhanced this experience. Some of the most memorable scenes in the movie are those when Marianne paints Héloïse. Marianne’s makeshift studio is a cavernous, and mostly empty room with light blue walls. Light floods into the room through the giant windows. Héloïse sits still in a flowy, forest green dress as Marianne observes her and paints. The portrait sessions give them an excuse to look at each other closely and without interruption. Marianne tries to capture every detail of Héloïse’s face, not just for the portrait but for herself. Every time that Marianne looks up from the canvas, Héloïse tries to catch her gaze so that she can savor every moment she has with Marianne. We do not only witness this interaction, but also experience it through close-ups. The theater screen magnifies their faces and the physical magnification also magnifies the emotions. The larger than life intimacy shown on the cinema screen guides us to inhabit Marianne as she stares at Héloïse, and Héloïse as she watches Marianne paint.

Traditionally, cinephiles see the gaze as an objectifying force. The new cinephile, however, sees it as a powerful way to create empathy. The philosopher Michel Foucault offers a description of the gaze that aligns more with the new cinephiles’ definition. Foucault devotes the opening chapter of his book The Order of Things to an analysis of Las Meninas. Instead of focusing on the technical or historical aspects of the painting, Foucault focuses on the relationships between the gazes of the viewer, painter, and subject. He starts by describing the painter, Diego Velazquez, who is visible within the painting. Shortly after, he brings in the spectator into the description and analyzes what they’d see: “The painter’s gaze, addressed to the void confronting him outside the picture, accepts as many models as there are spectators; in this precise but neutral place, the observer and the observed take part in a ceaseless exchange”. The spectator takes the position of the models for Velazquez’s paintings which we can assume are the King and Queen. This is confirmed by the mirror to the right of Velazquez that displays the upper bodies of the king and the queen. The spectator is both within the painting and outside of it. Portrait of the Lady on Fire has a similar effect on the viewer, but it is amplified by the film’s ability to imitate life. Through the depiction of the creation of another visual medium the film creates a complex and nested web of gazes.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire inhabits a space between Shambu’s and Quandt’s definitions of cinephilia. It values the aesthetic inclinations of traditional cinephilia while also subverting this male-dominated cinephilia by using the gaze to engender empathy rather than objectify. The exchange of looks between Héloïse and Marianne match the voyeuristic tendencies of the filmgoer and the film satisfies this voyeuristic urge by inviting the viewer to be part of the exchange. This aspect would excite the old cinephile because it takes full advantage of the visual medium. However, the film does not seek to satisfy the male gaze by fulfilling a sexual fantasy for the straight male viewer. Instead, it acknowledges the women’s sexuality while also respecting it. The film uses the viewers’ voyeuristic tendencies to create empathy between the audience and the characters rather than objectify them . The new cinephile would love this because it humanizes the queer characters and takes advantage of film’s political potential by engendering empathy for a marginalized group. Its understanding of film’s tradition allows Portrait of a Lady on Fire to subvert the norms of old cinephilia to create something wholly new.

The experience of this magnification can only be simulated outside of a movie theater. During my second viewing, I did not feel the same sense of hypnosis because the TV screen did not dominate my field of vision like the theater screen did. The colors were not quite as vibrant, and the image quality was not as pristine since I streamed the film off Hulu. My laptop also kept displaying notifications that I could not turn off. Quandt would probably say that these imperfections would ruin the entire experience, but the experience remained special because I shared it with others and the film’s central themes were not lost despite the imperfections. New cinephilia does not solely appreciate film for its aesthetic merit but also for its social importance. Many people that I know saw Portrait of a Lady on Fire because of its queer characters, not because they knew of Celine Sciamma and her work. The inclusion of queer characters in high art film empowers those who identify with the characters. For this reason, the digitization of film increases love for film by making it widely available. Films may be best experienced in a theater, but the stories they tell help us make sense of our humanity so they should be shared in every way possible.

Films may be best experienced in a theater, but the stories they tell help us make sense of our humanity so they should be shared in every way possible.

Films are about looking. Humans make most of their observations about the world through eyesight. We’ve evolved to interpret emotion in facial expressions and eyes. So much of what we communicate is through body language, and films can display non-verbal communication that is not possible to describe in words. Understanding the limits of verbal communication, Portrait of a Lady on Fire uses close-ups and the motif of painting portraits to underscore the importance of looking. Films exist in the present tense. Just like Marianne fails to paint Heloise from memory, film viewers cannot reproduce films from memory. Like the presence of another person, films can only be experienced in the moment. I love this ephemeral quality of film.

I love Portrait of a Lady on Fire for reminding me of the simple pleasure of just looking. I love films that say the most when there is no dialogue. I love when actors speak with their eyes. I love that film can make us appreciate the small details by magnifying its subjects. I love close-ups that are impossibly close, and I love landscapes that are larger than life. I love movie theaters with their pitch-black darkness and their giant screens. I love the internet for teaching me to love film. I love Blockbuster Video for introducing me to film and I love streaming for making the possibilities endless. My love for film is constantly evolving. Films have taught me how to see.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. “Upon Leaving the Movie Theater.” Cinematographic Apparatus: Selected Writings, edited by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Tanam Press, 1980, pp. 1–4.

Quandt, James. “Everyone I Know Is Stayin’ Home: The New Cinephilia.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, vol. 50, no. 1/2, 2009, pp. 206–209.

Shambu, Girish. “For a New Cinephilia.” Film Quarterly, 1 March 2019, pp. 32–34.

Diego Duckenfield-Lopez is a staff writer

dduckenfieldlopez24@amherst.edu

Cecelia Amory ’24 is a staff artist

camory24@amherst.edu