By AWA DIOP

Every Sunday at dusk, her moans dragged down our Sunday sun and beckoned it to set. The unnatural sound always rang too loud and plastered to every inch of space. Its wa v e s showered rice fields and disturbed calm rivers miles away. Once in a while, she interrupted her howls to release a shrill that sliced through the silence of the village. It stunted the flock of birds migrating Westward, frazzling them into different directions. The noises contorted faces into pity, annoyance and fear. She frightened us children to run home and tuck under our mother’s bosoms. Mama always shooed me away, so every Sunday I ran to Aunty Mina’s arms who received me with a stealthy laugh. She thought my fear was nonsensical, but never loosened her grip on my small frame.

I believe her name is Assa. Or perhaps it is Aïssa. It’s been a while since anyone has referred to her by her name. Whenever Mama whispered it to Aunty Mina, her tired tongue never allowed any of the syllables to properly fall out of her mouth into my ears. Her real name is not important anyways, because my friends and I have given her a new one. Chief Toto’s Shooba. She was the third wife of the Chief, married a month ago. I’ve only seen her once. Mama did not want me getting in grown people’s business, but I was with Aunty Mina the Thursday Shooba moved to our village, Kolikoro. Aunty Mina had to see and know everything, and Mama thinks I’m just like her. True and false information lovers is what she calls us.

Shooba was a tall woman. If I had to guess, I would say she was taller than Aunty Mina. According to Aunty Mina, her back is hunched, so she must be even taller than I saw. Aunty Mina also said she was old. Too old to just get married. Apparently, she was twenty-seven years. Fifteen whole years older than me. Aunty Mina says no one in her old village wanted to marry her despite coming from the wealthiest family of Sanagerè, so she must have had some problems. Her guess was that she could not have children or something. She thought the Chief Toto was getting married for money, and I believed it when they said there was to be no ceremony for the wedding. She told me to never let myself get that old before marriage. I remained silent, but nodded my head vigorously.

The first Sunday after her marriage, we heard a sharp cry at sundown. Mama assumed Aunty Adja, her close friend seven mudbrick huts down, was going into labor and having her fifth-baby. She ran to grab her waxy scarf to tie around her head and quickly washed her hands of the dinner ingredients. She directed me to grab the gift basket in the living room, and together we ran to her friend’s side. But as we got closer to their hut, Aunty Adja herself was trying to locate the persistent moans and screams.

As curious faces peaked out from behind curtains, the eyes of the villagers started to trail towards the Chief’s compound. Some bold villagers went closer to inspect the issue, many ready to offer a helping hand. As a medic walked out, his lifting of the heavy curtain amplified the noises behind him. He reassured everyone that all was well, and to excuse the disturbance that he promised, was to end soon. It lasted for another four hours.

Perplexed all four hours, the villagers came up with all sorts of theories. Questions floated around: Did something happen to one of the Chief’s wives? Which one was it? Could it be the Shooba giving birth? Aunty Adja had proposed her own theory that the third wife had some chronic illness. When the loud noises finally subsided, total silence fell over the village. No final answer was reached, but Chief Toto’s compound was the talk of the village for days. Nor the Chief or any of the three wives whispered a word of the incident. By that Thursday, the odd incident was forgotten. Until it happened again, at the same time, from the same compound. The rumors came back, with more fuel than ever. The villagers were determined to get answers.

It wasn’t until this most recent incident, that I heard anything concrete. Maié, my best friend, told me she mustered the courage to peek inside Chief Toto’s compound. Specifically, she saw inside Shooba’s hut. She said the moan slipped from the Witch Wife’s small lips, as she hunched over in pain. She described her discolored back as aged and tired, as if the skin had been relentlessly tugged on for years. Naked on the floor of the mudbrick hut, something solid and white leaked from her tired, rotten left breast. The right one, according to Maié, looked perfectly young and normal.

As the stuff leaked, it pierced through her nipple and sliced its opening each time. She jerked from each sharp jab. It was as if her bones were folding in on themselves, unable to sustain from the pain. Her pain revealed the volatility of human bodies, and Maié said she’s never seen any fold and shrivel like that. I imagine that the pain bruised and burned her bones. It must have probed at her flesh. Her tender nipple on her rotting boob must be on the verge of falling off every time it gets pierced.

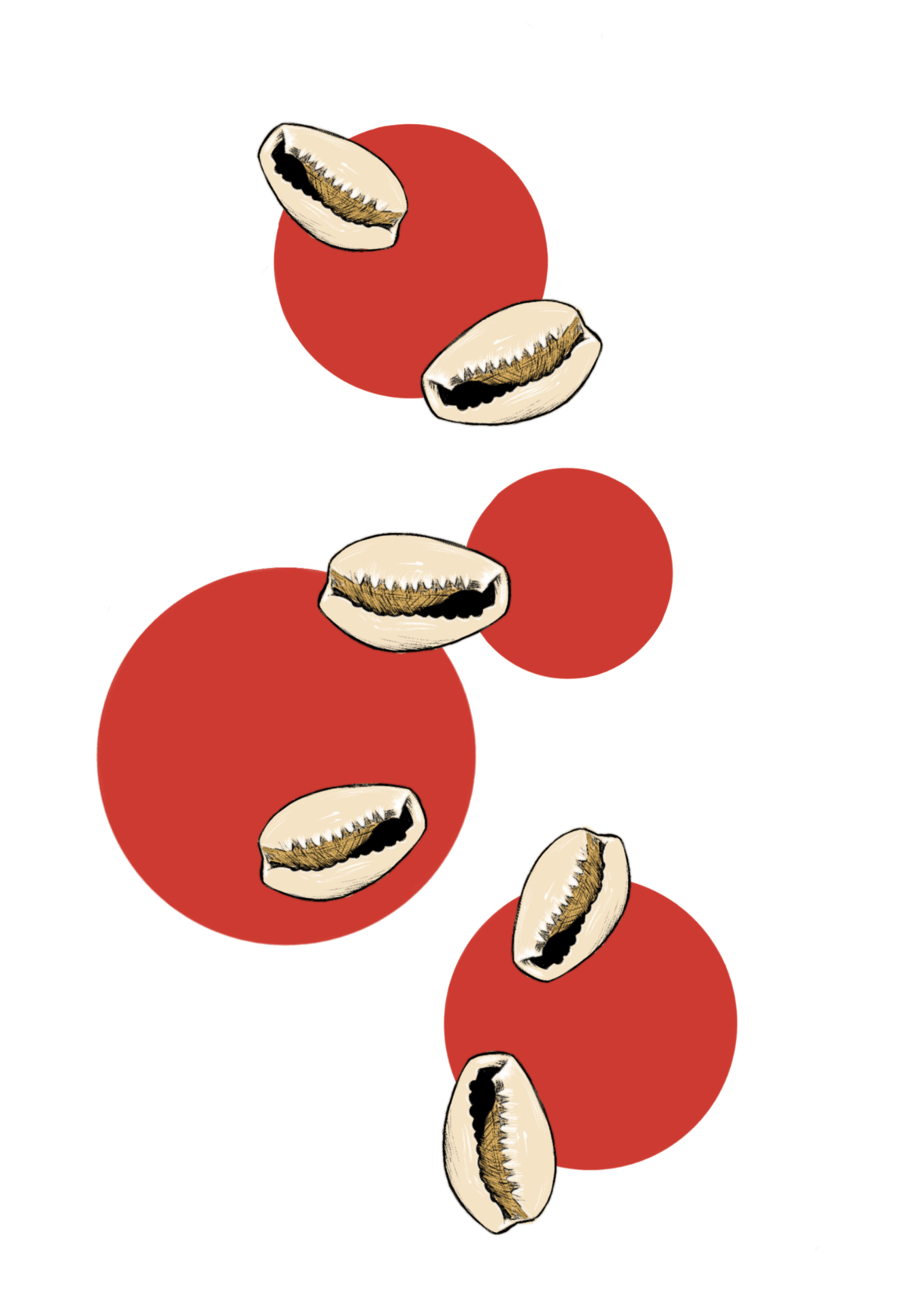

Maié swore they were cowry shells that she had seen her mother fondling around to fortune-tell. The shells were attached by strings of breast milk, and fell in curious patterns. Maié’s mother told her that these patterns from Shooba’s breasts told fortunes. She said that is why no one in her old village married her, for fear that she was a demonic spirit. Her mother believed she was a witch, which is why we named her Shooba.

Shooba never came out of her hut. I would not have believed she was real if not for that day I saw her. Yet, every Sunday for the past three weeks, she would moan and yell in pain to assert her presence in our village. Her moans never failed to frighten me, and her suffering disturbed my grounding.

Writer | Awa Diop ’26 | adiop26@amherst.edu

Editor | Mikayah Parsons ’24 | mparsons24@amherst.edu

Artist | Cecelia Amory ’24 | camory24@amherst.edu